With the growing use of IoT devices in industrial equipment, home automation, and medical applications, there is increasing pressure to optimize the power management portion of these devices—either through smaller form factor, better efficiency, improved current consumption, or faster charging times (for portable IoT devices). All of this must be achieved in a small form factor that does not negatively impact thermals nor interfere with the wireless communication implemented by these devices.

What Is IoT?

This particular IoT application area comes under many different guises. It generally refers to a smart, network connected electronic device that is likely battery-powered and sends precomputed data to the cloud-based infrastructure. It utilizes a mixture of embedded systems such as processors, communication ICs, and sensors to collect, respond to, and send data back to a central point or other node in the network. This can be anything from a simple temperature sensor reporting room temperature back to a central monitoring area, all the way up to a machine health monitor that tracks the long-term health of very expensive factory equipment.

Ultimately, these devices are being developed to solve a particular challenge, whether that be to automate tasks that would typically require human intervention, like home or building automation, or perhaps to improve the useability and longevity of equipment in the case of industrial IoT applications, or even to improve safety if you consider condition-based monitoring applications implemented in structure-based applications such as bridges.

Example Applications

The application areas for IoT devices are almost endless with new devices and use cases being thought of every day. Smart transmitter-based applications gather data about the environment in which they sit to make decisions about controlling heat, setting off alarms, or automating particular tasks. In addition, portable instruments like gas meters and air quality measurement systems provide an accurate measurement through the cloud to a control center. GPS tracking systems are another application. They allow the tracking of shipping containers as well as livestock such as cows through smart ear tags. These comprise just a small area of cloud connected devices. Other areas include wearable healthcare and infrastructure sensing applications.

A significant growth area is industrial IoT applications, which are part of the fourth industrial revolution where smart factories take center stage. There’s a broad range of IoT applications that are ultimately trying to automate as much of the factory as possible, whether that be through the use of automated guided vehicles (AGVs), smart sensors such as RF tags or pressure meters, or other environmental sensors positioned around the factory.

From an ADI perspective, the high level IoT focus has been on five main areas:

- Smart health — supporting vital signs monitoring applications both at a clinical level as well as consumer applications.

- Smart factories — focusing on building Industry 0 by making factories more responsive, flexible, and leaner.

- Smart buildings/smart cities — using intelligent sensing for building security, parking space occupancy detection, as well as thermal and electrical

- Smart agriculture — using the technology available to enable automated farming and resource usage efficiencies.

- More information on these focus areas and the technologies available to support them can be found at analog.com/IoT

IoT Design Challenges

What are the key challenges facing a designer in the ever-growing IoT application space? The majority of these devices, or nodes, are being installed after the fact or in hard-to-reach areas, so running power to them is not a possibility. This of course means that they are totally reliant on batteries and/or energy harvesting as a power source.

Moving power around large facilities can be quite expensive. For example, consider powering a remote IoT node in a factory. The idea of running a new power cable to power this device is costly as well as time consuming, which essentially leaves battery power or energy harvesting as the remaining options to power these remote nodes.

The reliance on battery power introduces a need to follow a stringent power budget to ensure that the lifetime of the battery is maximized, which of course has an impact on the total cost of ownership of the device. Another downside to battery usage is the need to replace the battery after its life has expired. This includes not only the cost of the battery itself, but also the high cost of human labor to replace and possibly dispose of the old battery.

An additional consideration on the battery cost and size—it is very easy to just overdesign the battery to ensure that there is sufficient capacity to achieve the lifetime requirement, which is very often greater than 10 years. However, overdesign results in additional cost and size, so it is extremely important to not only optimize the power budget but also to minimize the energy usage where possible in order to install the smallest possible battery that will still meet your design requirements.

Power in IoT

For the purposes of this power discussion, the power sources for IoT applications can be seen as three scenarios:

- Devices that rely on nonrechargeable battery power (primary battery)

- Devices that require rechargeable batteries

- Devices that utilize energy harvesting to provide system power

These sources can be used individually, or alternatively combined if the application requires it.

Primary Battery Applications

You are all aware of different primary battery applications, which are also known as nonrechargeable battery applications. These are geared toward applications where only occasional power is used—that is, the device is powered up occasionally before going back into a deep sleep mode where it draws minimal power. The main advantage of using this as a power source is it provides a high energy density and a simpler design—since you don’t need to accommodate battery charging/management circuitry—as well as a lower cost, as batteries are cheaper and fewer electronics are required. They fit well into low cost, low power drain applications, but because these batteries have a finite lifetime, they are not well suited to applications where power consumption is a little higher, so this incurs a cost for both a replacement battery as well as the cost of the service technician required to replace the batteries.

Consider a large IoT installation with many nodes. As you have a technician on-site replacing the battery for one device, very often all the batteries will end up being replaced at one time to save the labor cost. Of course, this is wasteful and just adds to our overall global waste problem. On top of that, nonrechargeable batteries provide only about 2% of the power used to manufacture them in the first place. The ~98% of wasted energy makes them a very uneconomical power source.

Obviously, these do have a place in IoT-based applications. Their relatively low initial cost makes them ideal for lower power applications. There are loads of different types and sizes available, and as they don’t need much additional electronics for charging or management, they are a simple solution.

From a design perspective, the key challenge is making the most use out of the energy available from these little power sources. To that end, much time needs to be spent creating a power budget plan to ensure that the lifetime of the battery is maximized, with 10 years being a common lifetime target.

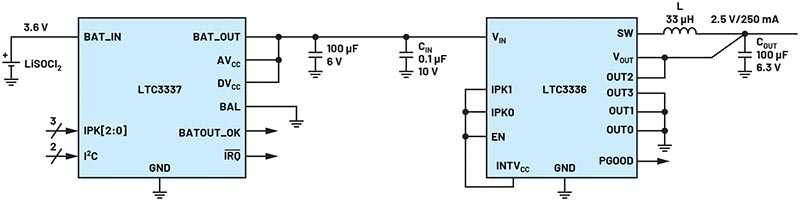

For primary battery applications, two parts from our nanopower family of products are worth considering—the LTC3337 nanopower coulomb counter and the LTC3336 nanopower buck regulator, shown in Figure 1.

The LTC3336 is a low power DC-to-DC converter running from up to a 15 V input with programmable peak output current level. The input can go as low as 2.5 V, making it ideal for battery-powered applications.

The quiescent current is exceptionally low at 65 nA while regulating with no load. As DC-to-DC converters go, this is pretty easy to set up and use in a new design. The output voltage is programmed based on how the OUT0 to OUT3 pins are strapped.

The companion device to the LTC3336 is the LTC3337, a nanopower primary battery state of health monitor and coulomb counter. This is another easy device to use in a new design—simply strap the IPK pins according to the peak current required, which is in the 5 mA to 100 mA region. Run a few calculations based on your selected battery, then populate the recommended output cap based on the selected peak current, which is noted in the data sheet.

Ultimately, this is a fantastic pairing of devices for IoT applications with a limited power budget. These parts can both accurately monitor the energy usage from the primary battery and efficiently convert the output to a usable system voltage.

Rechargeable Battery Applications

Let’s move on to rechargeable applications. These are a nice choice for higher power or higher drain IoT applications where primary battery replacement frequency is not an option. A rechargeable battery application is a higher cost implementation because of the initial cost of the batteries and the charging circuitry, but in higher drain applications where the batteries are drained and charged frequently, the cost is justified and soon paid back.

Depending on the chemistry used, a rechargeable battery application can have a lower initial energy than a primary cell, but on a longer term it is the more efficient option, and, overall, is less wasteful. Depending on the power needs, another option is capacitor or supercapacitor storage, but these are more for shorter-term backup storage.

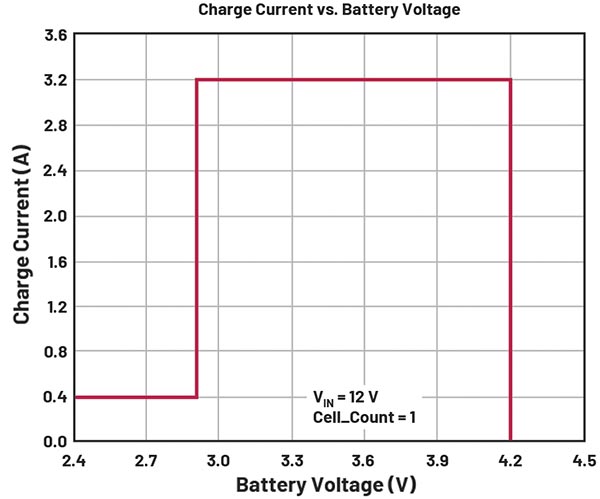

Battery charging involves several different modes and specialist profiles depending on the chemistry used. For example, a lithium-ion battery charge profile is shown in Figure 2. Across the bottom is the battery voltage, and charge current is on the vertical axis.

When the battery is severely discharged, as on the left of Figure 2, the charger needs to be clever enough to put it in precharge mode to slowly increase the battery voltage to a safe level before entering constant current mode.

In constant current mode, the charger pushes the programmed current into the battery until the battery voltage rises to the programmed float voltage.

Both the programmed current and voltage are defined by the battery type used—the charge current is limited by the C-rate and the required charge time, and the float voltage is based on what is safe for the battery. System designers can reduce the float voltage a little to help with lifetime of the battery if required by the system—like everything with power, it’s all about trade-offs.

When the float voltage is reached, it can be seen that the charge current drops to zero and this voltage is maintained for a time based on the termination algorithm.

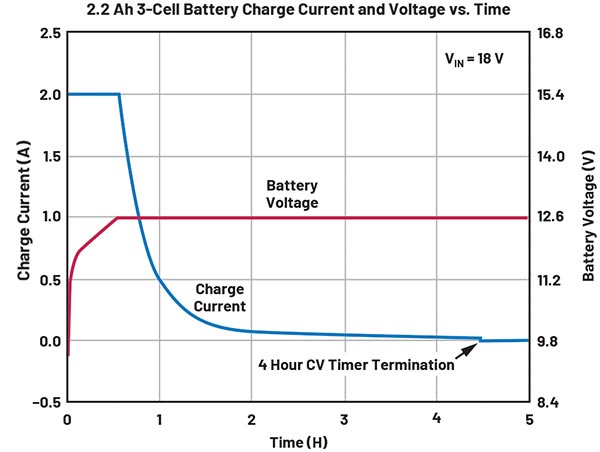

Figure 3 provides a different graph for a 3-cell application showing the behavior over time. The battery voltage is shown in red and charge current is in blue. It starts off in constant current mode, topping out at 2 A until the battery voltage reaches the 12.6 V constant voltage threshold. The charger maintains this voltage for the length of time defined by the termination timer—in this case, a 4-hour window. This time is programmable on many charger parts.

For more information on battery charging, as well as some interesting products, I’d recommend the Analog Dialogue article “Simple Battery Charger ICs for Any Chemistry.”

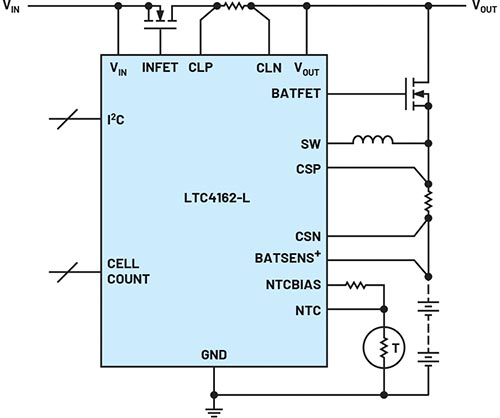

Figure 4 shows a nice example of a versatile buck battery charger, the LTC4162, which can provide a charge current up to 3.2 A and is suitable for a range of applications including portable instruments and applications requiring larger batteries or multicell batteries. It can also be used to charge from solar sources.

Energy Harvesting Applications

When working with IoT applications and their power sources, another option to consider is energy harvesting. Of course, there are several considerations for the system designer, but the appeal of free energy cannot be understated, especially for applications where the power requirements aren’t too critical and where the installation needs to be hands off—that is, no service technician can get to it.

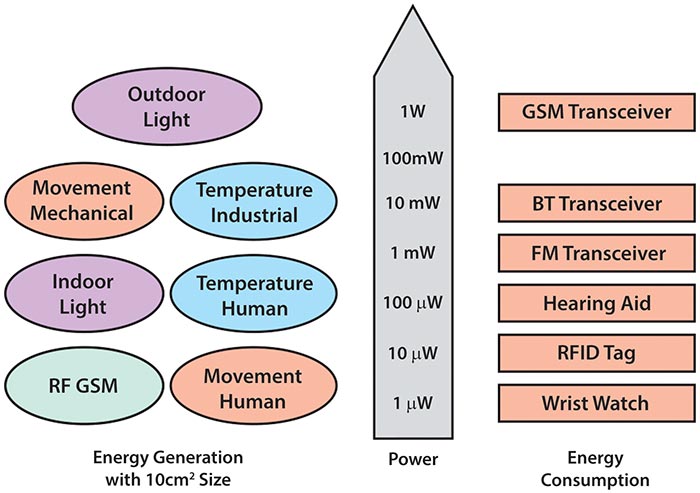

There are many different energy sources to choose from, and they don’t need to be an outdoor application to take advantage of them. Solar as well as piezoelectric or vibrational energy, thermoelectric energy, and even RF energy can be harvested (although this has a very low power level). Figure 5 provides an approximate energy level when using different harvesting methods.

As for disadvantages, the initial cost is higher compared to the other power sources discussed before, since you need a harvesting element such as a solar panel, piezoelectric receiver, or a Peltier element, as well as the energy conversion IC and associated enabling components.

Another disadvantage is the overall solution size, particularly when compared to a power source like a coin cell battery. It’s difficult to achieve a small solution size with an energy harvester and conversion IC.

Efficiency wise, this can be a tricky one to manage low energy levels. This is because many of the power sources are AC, so they need rectification. Diodes are used to do this. The designer must deal with the energy loss resulting from their inherent properties. The impact of this is lessened as you increase the input voltage, but that’s not always a possibility.

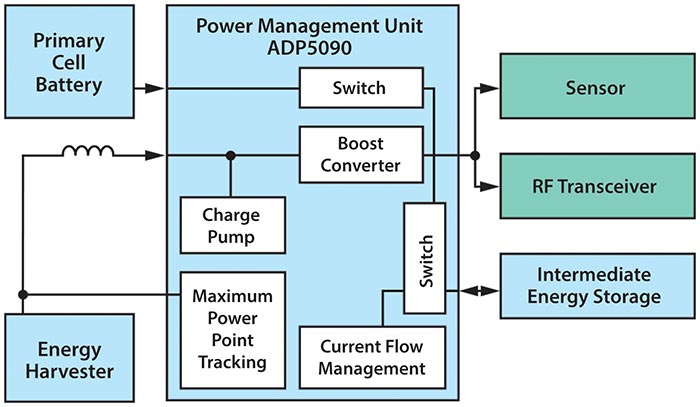

The devices that pop up in most energy harvesting discussions are from the ADP509x family of products, and the LTC3108, which can accommodate a wide range of energy harvesting sources with multiple power paths and programmable charge management options that offer the highest design flexibility. A multitude of energy sources can be used to power the ADP509x but also to extract energy from that power source to charge a battery or power a system load. Anything from solar (both indoor and outdoor) to thermoelectric generators to extract thermal energy from body heat in wearable applications or engine heat can be used to power the IoT node. Another option is to harvest energy from a piezoelectric source, which adds another layer of flexibility—this is a nice option to extract power from an operational motor, for example.

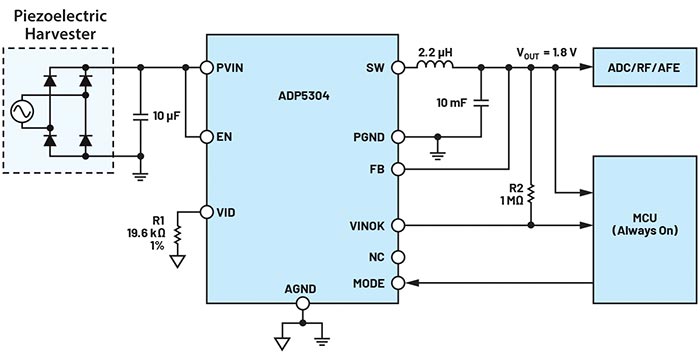

Another device that is capable of being powered from a piezoelectric source is the ADP5304, which operates with a very low quiescent current (260 nA typical with no load), making it ideal for low power energy harvesting applications. The data sheet shares a typical energy harvesting application circuit (see Figure 7), powered from a piezoelectric source and being used to provide power to an ADC or an RF IC.

Energy Management

Another area that should be part of any discussion relating to applications with a limited power budget is energy management. This starts with developing a power budget calculation for the application prior to looking at different power management solutions. This essential step helps system designers understand the key components used in the system and how much energy they require. This impacts their decision to select a primary battery, rechargeable battery, energy harvesting, or a combination of these as the power supply methodology.

The frequency of the IoT device gathering a signal and sending it back to the central system or cloud is another important detail when looking at energy management, which has a large impact on overall power consumption. A common technique is to duty cycle the power usage or stretch the time between waking the device up to gather and/or send data.

Making use of standby modes on each of the electronic devices (if available) is also a useful tool when trying to manage the system energy usage.

Conclusion

As with all electronic applications, it is important to consider the power management portion of the circuit as early as possible. This is even more important in power-constrained applications such as IoT. Developing a power budget early in the process can help the system designer identify the most efficient path and suitable devices that meet the challenges posed by these applications while still achieving high energy efficiency in a small solution size.

References

Dostal, Frederik. “New Advances in Energy Harvesting Power Conversion.” Analog Dialogue, Vol. 49, No. 3, September 2015.

Knoth, Steve. “Simple Battery Charger ICs for Any Chemistry.” Analog Dialogue, Vol. 53, No. 1, January 2019.

Murphy, Grainne. “Internet of Things (IoT): What’s Next.” Analog Devices, Inc., January 2018.

Pantely, Zachary. “One-Size-Fits-All Battery Charger.” Analog Devices, Inc., September 2018.

Author:

Diarmuid Carey,

Central Applications Engineer

Diarmuid Carey is an applications engineer with the European Centralized Applications Center based in Limerick, Ireland. He has worked as an applications engineer since 2008 and joined Analog Devices in 2017, providing design support for the Power by Linear portfolio for European broad market customers. He holds a Bachelor of Engineering in computer engineering from University of Limerick. He can be reached at diarmuid.carey@analog.com.

Analog Devices

Contact Romania:

Email: inforomania@arroweurope.com

Mobil: +40 731 016 104

Arrow Electronics | https://www.arrow.com