Power modules are the way to go when it comes to leveraging the expertise of power experts and getting your design to market quickly, but choose wisely. Power-module architecture choices can greatly affect your power supply’s performance.

By Jian Yin, Intersil Corporation

Introduction

Whether evaluating step-down switching regulators at the silicon-level (controller with FET), or power modules where the integration, and ease of use of a more complete power supply subsystem may be preferred, system designers everywhere are under enormous pressure. They’re being tasked with integrating more power and features in ever-shrinking form factors, and thus adversely affecting the system’s electrical and thermal characteristics.

There are various obstacles system designers must overcome on the path to integration nirvana. These include the increased likelihood of noise coupling as components are in closer proximity, as well as heat dissipation, given that the power-handling capabilities continue to increase along with smaller footprint areas.

Fortunately, power module designers continue to innovate to meet these demanding requirements through various architectural and topological design approaches that extract the maximum performance from the smallest package. Yet, these innovations put the burden upon system designers in need of the optimum power module to be careful in their choice of solutions. The techniques used by different power module solutions can greatly affect overall system cost, as well as key performance parameters such as heat dissipation, transient response, ripple voltage, and even ease of use. It’s very much a case of ‘buyer beware’.

The Case for Modular versus Discrete

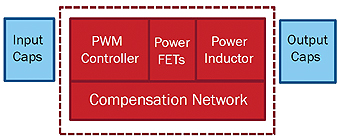

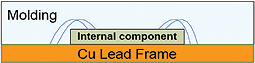

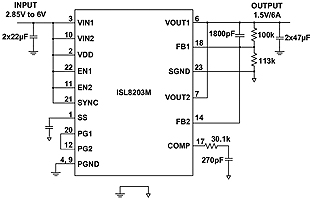

For system designers, there are many reasons to opt for a power module versus designing a power converter from the component level, not least of which are ease of use and time-to-market. By adding only input and output capacitors, these power customers can finish their designs relatively easily and quickly, with confidence that their basic performance and space requirements have been met. The power module is a complete power converter system in an encapsulated package that includes a PWM controller, synchronous switching MOSFETs, inductors and passive components, see Figure 1.

For example, Intersil’s ISL8203M power module has an extremely low profile package at 1.83mm, which is similar to a 1206 capacitor’s height. Also, it delivers the excellent electrical and thermal performance to meet all customer requirements. Normally that knowledge would be sufficient, but how that module was designed can greatly affect more nuanced parameters, features and capabilities.

ISL8203M Deep Dive

ISL8203M is a complete DC-DC power module that has been optimized to generate low

output voltages ranging from 0.8V to 5V, making it ideal for any low-power, low-voltage applications. The supply voltage input range is from 2.85V to 6V. The two channels are 180° out-of-phase for input RMS current and EMI reductions. Each channel is capable of 3A output current. These channels can be combined to form a single 6A output in current-sharing mode. While in current-sharing mode, the interleaving of the two channels reduces input and output voltage ripple.

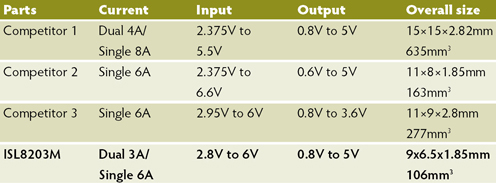

ISL8203M is only 1.83mm thick with a footprint of 6.5mm × 9mm, as shown in Figure

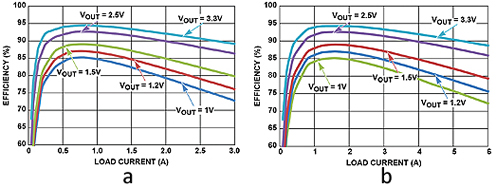

2. It has the most compact package profile for a given input and output voltage/current range, see Table 1, and its overall package volume is only 106mm3, which is dramatically smaller than all other power module solutions. Although the ISL8203M package is very compact, it is still delivers very good efficiency, as shown in Figure 3.

Small Module Package Offers Excellent Thermal Performance

The ISL8203M uses a QFN (quad-flat, no-leads) copper lead-frame package, where the internal component is soldered directly to the copper lead frame, see Figure 4.

Also, the wire bonds can be applied to the top of the internal component for electrical connections to the lead-frame. Then the molding can be filled in to form a complete encapsulated package.

This structure allows the heat generated by the internal components to be dissipated directly by the copper in the lead frame which has a thermal conductivity of ~385 W/mK. This is about 1000 times the thermal conductivity of the printed circuit board (PCB) which has a typical thermal conductivity of ~0.343 W/mK.

As a result, the copper-based lead frame can help the heat dissipate much more efficiently than a PCB-based module.

Also, since the copper lead frame can be six times thicker than the 1oz copper on a typical PCB, the module lead frame can help spread the heat over a large area, thus accelerating the effective heat transfer area to the system board.

Overall, the module’s thermal performance can be better than a discrete solution where the component is soldered directly to the PCB system board.

It’s important to note that the molding material in the structure can have a similar heat-spreading effect to the copper lead frame. Although the molding material has a lower thermal conductivity, the heat can still transfer through the molding horizontally and then dissipate into the copper lead frame. The molding also increases the effective heat transfer area from the internal power component, and thus decreases the thermal resistance from the internal part to ambient. This is another important comparison benefit of power modules – the ability to handle high power in a small package versus discrete solutions.

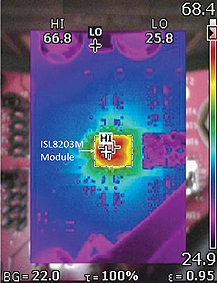

Let’s take a closer look at the thermal performance of an ISL8203M mounted on a standard four-layer evaluation board with 2oz. copper on the top and bottom layers, and 1oz. copper in the middle layers, see Figure 5. Running a worst-case scenario of 5Vin to 3.3Vout/6A with no airflow and an ambient temperature of 25°C, the module’s maximum temperature is only 66.8°C.

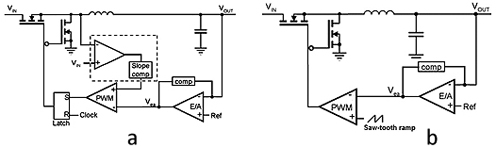

For Transients, Current-Mode Power Module Achieves Better Performance

There are generally two types of control schemes used in module applications: current-mode and voltage-mode. To ensure a fast transient response under various load conditions, the ISL8203M uses a current-mode control scheme to regulate the output voltage, see Figure 6. The scheme’s current-sensing signal is derived from the voltage across the top FET’s conducting resistance (Rdson) of the synchronized buck converter. This is then fed into the current amplifier, the output of which undergoes slope compensation before being compared to the output error amplifier to generate what now becomes the pulse-width modulation (PWM) signal. Through the driver, the PWM signal can control the synchronized buck converter to achieve the required voltage regulation. The compensation on the error amplifier is needed to boost the loop gain and phase margin to achieve better performance and stability.

The structure of the voltage-mode control is simpler than current-mode control. It replaces the dashed block area in Figure 6 (a) with a saw-tooth ramp at a fixed frequency shown in (b). This saw-tooth ramp, instead of the current-mode design’s current-sensing signal, is then compared with the error amplifier’s output to generate the required PWM signal.

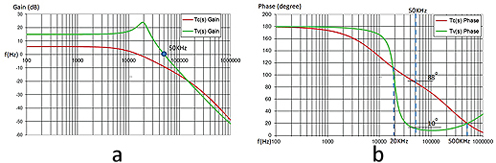

The voltage mode control is also easy to understand. As shown in the figure 7, its open-loop system is a two-order system, with the inductor and output cap forming the complex poles. Clearly, its normalized phase Tv(s), shown in Figure 7 (b) drops very fast by 180° across the 20kHz resonant frequency of the complex poles. This system depends upon the compensation components to improve the phase margin to achieve stability. Otherwise, it only has 10° phase margin with the crossover frequency at 50kHz, as shown in Figure 7 (b). Large phase margin (typically higher than 40°) is a necessity for the loop stability.

If we use this same voltage-mode control system in (a) and modify it to the current loop shown in Figure 6 (a), it becomes a current-mode control system. The system open-loop Bode plot is shown in Figure 7 as Tc(s). This system is close to a single-order system at the low frequency range, so the phase is boosted dramatically from 20kHz to 500KHz, shown in Figure 7 (b).

Even without the compensation components, this is still a stable system. If a simple type II compensation is added to improve the low-frequency gain and push the crossover frequency to about 50KHz, the current-mode control phase margin can still be about 80°, which is sufficient for stability. So, for current-mode control, the compensation is relatively simple, versus voltage mode, and can cover a wide range of different output capacitors due to the large phase boost in open loop.

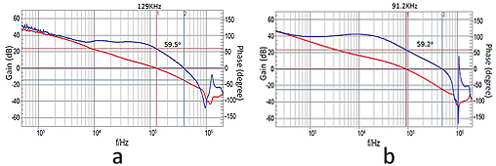

For power-module applications, the compensation is fixed inside the package, so if the output capacitors are changed with different customers’ applications, the complex poles in the voltage-mode control can be shifted significantly. The fixed compensation may not cover the wide range of output-capacitor changes since its open-loop phase is too low once over the LC resonant frequency. So in many cases, it can cause insufficient phase margins if the load conditions are changed. To avoid this, the voltage-mode module must lower the loop bandwidth (cross-over frequency) to ensure enough phase margin for stability at various load conditions compared to current-mode control. The penalty for lowering this bandwidth is poor transient response performance. To show this critical difference in transient performance, we selected one competitor’s 4A power module with voltage-mode control to compare with ISL8203M. The final loop Bode plots of these two power modules are shown in Figure 8.

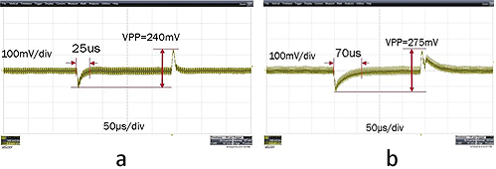

If we select the same output capacitors for the test, with the phase margins both at ~60°, the ISL8203M loop bandwidth of one 3A output was much higher than the voltage-mode module, leading to the ISL8203M having much better transient performance, see Figure 9.

Under the same testing conditions, the ISL8203M has a peak-to-peak variation of 240mV and a recovery time of only 25µS, while the voltage-mode module has a peak-to-peak variation at 275mV and large recovery time of 70µS.

Paralleled Operation Provides Low Output Ripple

Finally, the ISL8203M can operate with dual 3A outputs or a single 6A output. When it runs at 6A, the two 3A outputs can be paralleled as shown in Figure 10. With the

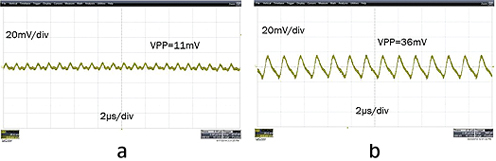

phase interleaving between two outputs at 180°, the input and output ripples can be reduced dramatically. As shown in Figure 11, the paralleled output ripple is only 11mV, while the competitor’s single-phase module ripple goes as high as 36mV, under the same test conditions.

More importantly, for a given output ripple, the ISL8203M needs less than half of the output capacitors compared to the single-phase module, thus providing significant cost savings.

Conclusion

The ISL8203M comes in a compact package yet still meets customers’ electrical and thermal performance requirements. The module’s standard evaluation requires no heat sink and no airflow, delivers a total power of 20W to the load, with the module reaching a maximum temperature of only 66.8°C.

Its current-mode control scheme allows the ISL8203M to achieve good transient performance with excellent peak-to-peak variation and a recovery time that is one-third that of competitive power modules. The ISL8203M’s special parallel mode also enables it to deliver 6A, with extremely low output ripple, and two outputs interleaved at 180°. This feature also comes with significant component cost savings for a given ripple limit. With all of these superior performance characteristics, the ISL8203M is a good candidate for any low-power, low-voltage application, such as test and measurement, communication infrastructure and industrial control systems, all requiring high density and good performance.

To meet the challenges of designing the power subsystem for these systems, many designers are using power modules instead of traditional discrete point-of-load designs, when time-to-market, size constraints, reliability and design capabilities are the motivating factors. Find out more about Intersil’s ISL203M power module at the web page: www.intersil.com/products/ISL8203M ■

About the Author:

Jian Yin is the Applications Engineering Manager for Industrial and Infrastructure Products at Intersil Corporation. He is responsible for analog and digital power module design and development, and all power module related customer applications support. Mr. Yin is the recipient of eight U.S. patents (including pending patents), and has published over 50 journal articles and technical papers. Prior to joining Intersil, Mr. Yin was a Senior Engineer at Monolithic Power Systems and a Module Design Engineer at Linear Technology Corporation, where he designed and released more than nine power module products. Mr. Yin holds a Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Intersil Corporation

www.intersil.com